By Wang Yang and Guo Baoyi

Over the past decade (2011-2024), the term “independent animation” 独立动画 has been widely applied in animation production, academic research, media reports, and festivals/exhibitions in China. However, due to an overlapped context of aesthetic and production perspectives, the definition(s) of “independence” 独立 towards independent animation is(are) still unclear and polysemous, consequently obscuring scholarly thinking in conceptual genealogical research.[1]

To elaborate, firstly, as “independent animation” was once relatively new in China, it failed to form a clear and authentic definition. In discussions around 2012-2013, the term was noted as being traceable back to the 2008 Beijing Independent Film Festival 北京独立影像展.[2] During the same period, curators such as Pi San (aka Wang Bo), Dong Bingfeng, and Wang Chunchen began organizing exhibitions under the banner of “independent animation” (esp. 2012 Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale 首届深圳独立动画双年展), which initiated the opinion that it was within biennale discourse that the term started to be academically defined.[3] Then, a decade later, in 2025, Cao Kai further couples this concept with the so-called spirit of the “Chinese School” 中国学派 under the name of “contemporary animation” 当代动画.[4]

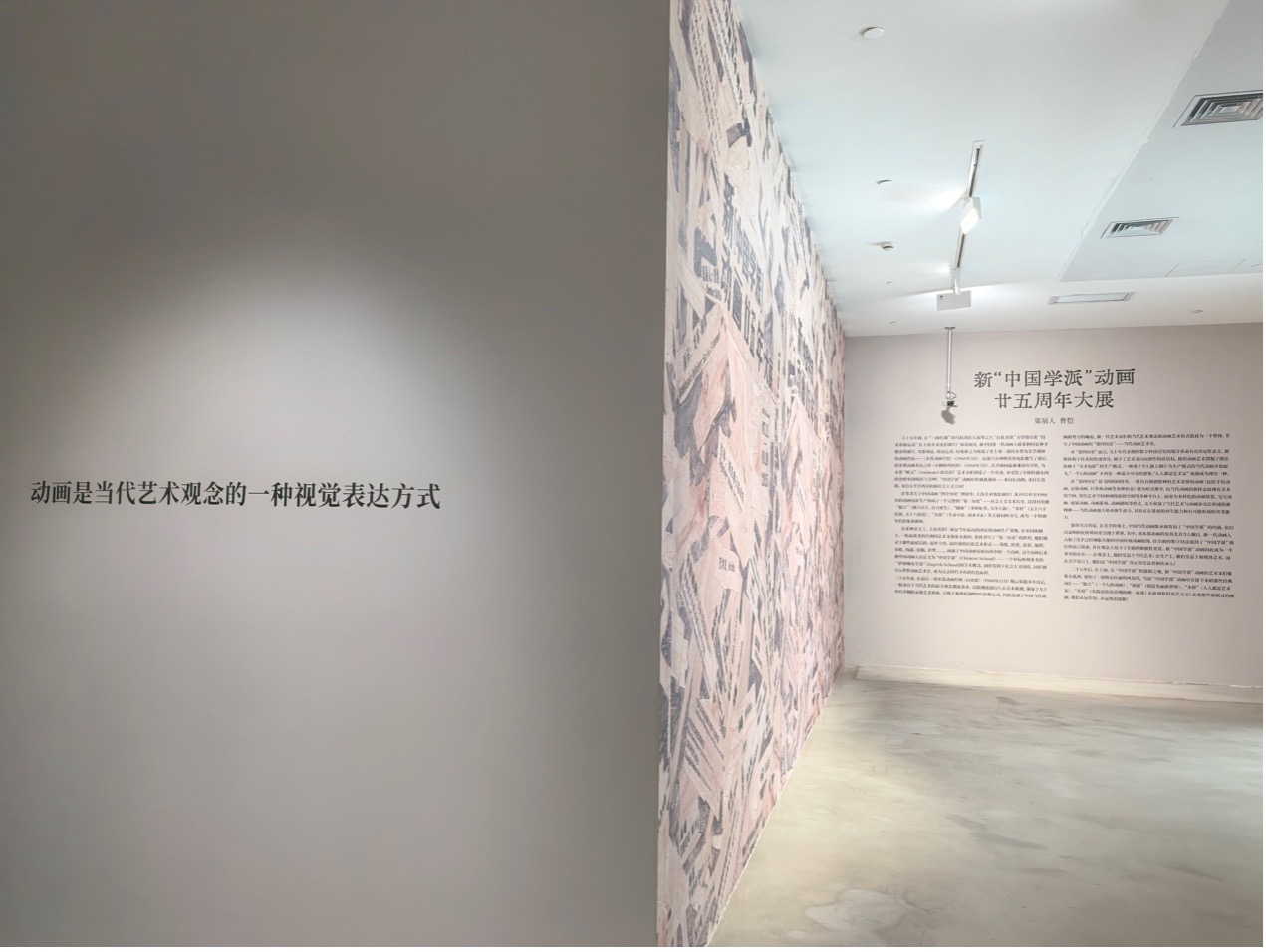

Figure 1. On-site landscape of the “25th Anniversary Exhibition of The New Chinese School” 新“中国学派”动画廿五年大展, BEING Art Museum. (Source Guo Baoyi, photo taken on August 28, 2025.)

Secondly, pursuing parallel approaches, domestic scholars then often discuss independent animation from an independent film and/or a contemporary art view, arguing that early independent animation directors followed a non-mainstream working approach. Therefore, related terms include but are not limited to “experimental animation” 实验动画, “min-jian animation” 民间动画, “self-produced animation” 个人动画, “auteur animation” 作者动画 and “minor animation” 小众动画 emerged. For example, Dong highlights that these works are deeply anti-establishment; in contrast to the commercial discourse.[5] Wei believes that they are partly “non-academic” 非学院.[6] Chen positions independent animations as the art ones that “do things according to one’s own willingness for self-expression but not serving the profit.”[7] Auteur animation’s artistic autonomy, despite its marginalized status in the entire film field, is also discussed.[8]

Thirdly, domestic studies concerning animation production have not been well developed. As to general animation production 动画制片, Zheng and Yu approach the term from a decision-making view, defining it as animation business management or as animation project development.[9] As to independent animation production 独立动画制片, Wang states that these kinds of animations have to be made by individuals or small-scale studios,[10] while Xue reductively categorizes works embedded with “individual completion of directing and screenwriting” 一人独立完成编导 attributes as non-mainstream animation.[11] Moreover, only a few studies regard the process of production as a part of independent animation creators’ “creative ecology” 创作生态.[12]

Therefore, on the one hand, aesthetically, “independence” refers to a work-based judgment, and independent animations are considered the non-business-oriented auteur’s works 作者作品.[13] On the other hand, being different from the large-scale studios, “independence” also refers to individual/small-scale production, distribution and promotion. Along these lines, several dualistic paradigms have been derived from domestic discourse on “independence vs. dependence” 独立-非独立 in the context of independent animations. Particularly, they are: “min-jian vs. official” 民间-官方, “grassroots vs. school” 草根-学院, “low culture vs. high culture” 低俗-高雅, “experimental vs. non-experimental” 实验-非实验, “non-profit vs. commercial” 非盈利-商业化 and “personal creation vs. team production” 个人创作-团体生产.

However, aside from the frequent use of these dichotomies, domestic scholars have not explored their original causes, historical backgrounds and changing processes, not to mention their respective references in the aspects of aesthetics and production. More importantly, due to recent findings and breakthroughs of Chinese independent animations at home and abroad, the previous trial of defining independent animation production has become less appropriate.

Specifically, observing the widely-known career possibilities of independent animation artists (e.g., Chen Lianhua, Lei Lei), the potential business opportunities of making independent animated features/series (e.g., To the Bright Side 向着明亮那方, 2021; Yao-Chinese Folktales 中国奇谭, 2023; and Bilibili’s Capsules Project 胶囊计划, 2022-ongoing), the prosperous independent animation-oriented exhibitions (e.g. Feinaki Animation Week 费那奇动画周, 2019-ongoing), and the remarkable theatrical distribution cases in China (e.g. Have a Nice Day 大世界, 2017; The Summer of Mermaid 美人鱼的夏天, 2024; Art College 1994 艺术学院, 2025), we need more systematic and up-to-date research.

In this paper, we aim to investigate the changes and links of those aforementioned dichotomies by looking into historical practices, Internet empowerment and the business environment of independent animations in China. Additionally, taking the domestic independent film theories and the worldwide animation production routines as references, we also aim to find out the connotations and differences between “aesthetic independence” and “independent production” in the Chinese context. For a solid research outcome, we then review extensive sources including monographs, academic papers, forum speeches, lecture notes, exhibition catalogs, interview reports and other topic-relevant materials.

Historical Practices: the Establishment of “Min-jian vs. Official” and the Emergence of “Experimental vs. Non-experimental”

The establishment of “min-jian vs. official” is closely bound up with a Shanghai Animation Film Studio (SAFS)-centered Chinese animation history. Notably, the SAFS influences are threefold: (1) before SAFS was established (ca 1920s-1930s), several independent animation productions with official background were omitted; (2) during the SAFS heyday of team production (ca 1950s-late 1980s), a director-centered mode was emphasized; (3) after SAFS was influenced by the Chinese economic reform (ca late 1980s), the studio and its staff members embraced the free spirit and contributed to an independent production trend.

As one of the most representative state-owned film studios during the Planned Economy Period, the SAFS crew (former mei-shu film group of Dongbei Film Studio 东北电影制片厂美术片组) has been known for animation works with distinctive Chinese characteristics.[14] On one hand, the advantages of centralized creation, such as “favorable system” 体制优越 and “stable structure” 结构稳定, contribute to SAFS’s high-quality production.[15] On the other hand, following the nationalism-oriented ideology, the Ministry of Culture 文化部 once formulated a “serve the children and teenagers” 为少年儿童服务 guideline for mei-shu films, and SAFS proposed the slogan “explore the path of Chinese style” 探民族风格之路 in response.[16]

Therefore, SAFS animations not only reflected an official and national aesthetics boom, but also made outstanding achievements for Chinese animation history. For instance, Pigsy Eats Watermelon 猪八戒吃西瓜 (1958), Baby Tadpoles Look for Their Mother 小蝌蚪找妈妈 (1960) and The Monkey King 大闹天宫 (1961-64) have enjoyed international reputation; Wang Shuchen 王树忱, director of Prince Nezha’s Triumph Against Dragon King 哪吒闹海 (1980), once led a Chinese delegation to attend the 1980 Cannes Film Festival. However, Cao points out that expendables such as celluloid and photographic equipment had been monopolized by the state until the late 1980s.[17] In this vein, there was no true “independently-made animation” at that time.

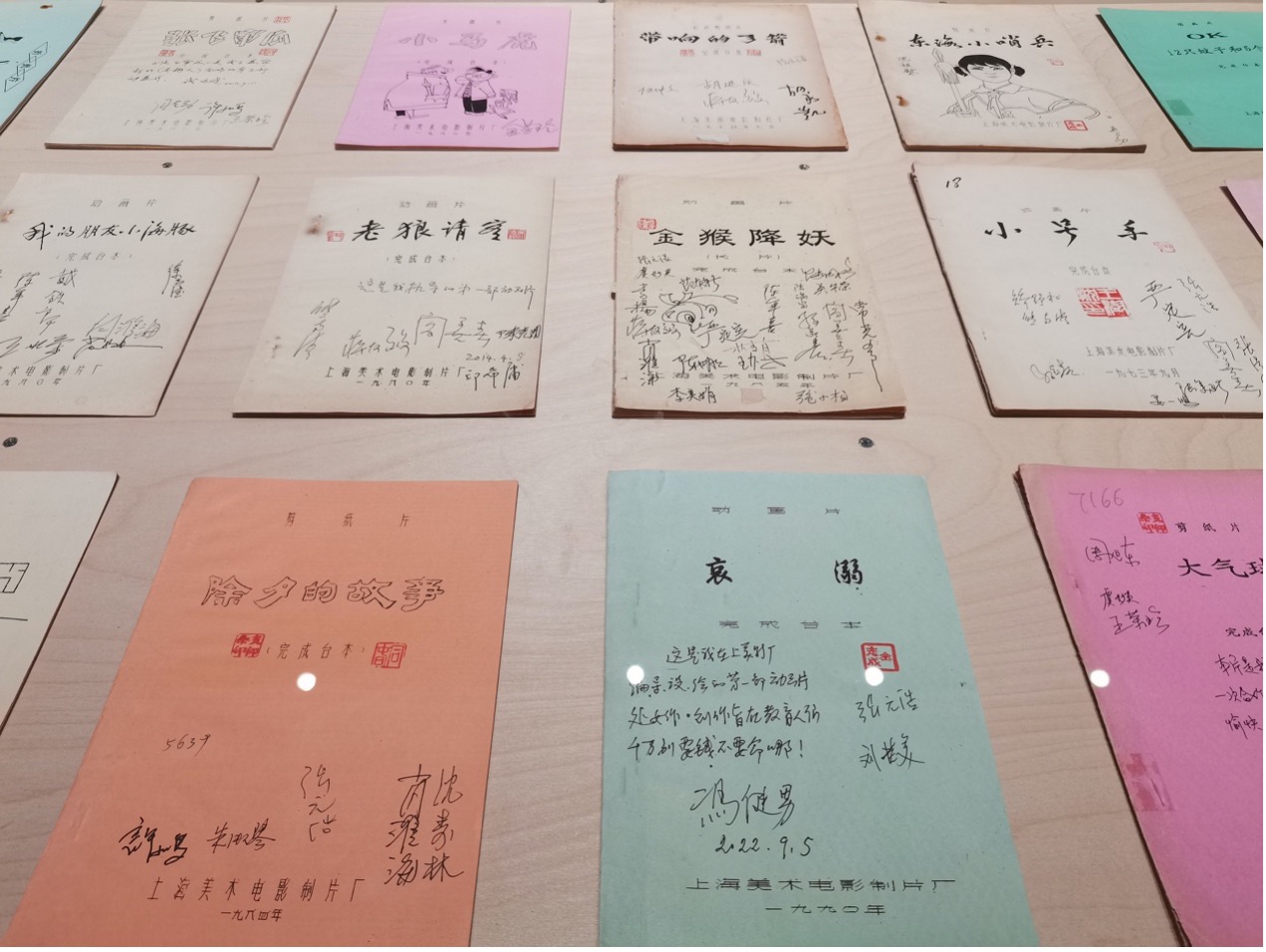

Even though in the 1980s, some SAFS artists took a crack at producing independent animation. At the 1988 Shanghai International Film Festival 上海国际动画电影节, this trend reached a peak. In sequence, personal creations or small-scale team productions gradually diverged from the SAFS-representative official routine. Thereby, during the 1992 Shanghai International Film Festival, the number of short animated films made by SAFS artists increased, featuring film studios, animation companies and even individuals all over China.[18] Among them, Pu Jiaxiang 浦稼祥 who just retired from SAFS made Watching Peking Opera 看戏 (1991) – a Chinese ink wash painting style animated film – at his own expense; Sun Zhe 孙哲 directed Grass 小草 (1992), which was sponsored by Beijing Glorious Animation Company 北京辉煌动画公司; and the under-reform SAFS also tried to produce low-cost works, which were witnessed by short films such as Desert Wind 漠风 (1992), OK (1992), and The Cat and the Rat 猫与鼠 (1992).

Figure 2. We can see the script for OK is located in the upper right corner. From “Animating China – A History of Shanghai Animation Films” 绘动世界——上海美术电影的时代记忆与当代回响, Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum. (Source Guo Baoyi, photo taken on August 27, 2024.)

Despite this, of particular relevance to SAFS, film studios or animation companies, the cases above are rarely described as min-jian works by Chinese scholars. For example, Wu suggests that it is the 2001 Beijing Independent Film Festival 北京首届独立映像节 that links “min-jian” to “unofficial”, where remarkable independent animation artists such as Meng Jun 孟军 (TALK聊天, 2001) and Ultra Girl Studio (I Love U 我爱你, 2001) took part.[19] Besides, Cao regards the festival from a film production-centered view, seeing it as an output simultaneously influenced by the New Documentary Movement 新纪录片运动 (1980s-1990s), video art and the sixth generation of Chinese filmmakers.[20] In other words, it is not very relevant to animation.

Nevertheless, in opposition to the “official” tag of SAFS’s heyday, we argue that the late 1980s personal creations of SAFS staff members already have an “unofficial” attribute, and it strongly confirms the “min-jian vs. official” paradigm. Meanwhile, we also argue that the SAFS system has an exclusive contribution to the establishment of this paradigm to a certain extent.

Specifically speaking, before the founding of SAFS, government-supported animations such as the Wan Brothers 万氏兄弟’ Kang Zhan Ge Ji 抗战歌辑 (1938) and Kang Zhan Biao Yu 抗战标语 (1938) and Qian Jiajun 钱家骏’s Nong Jia Le 农家乐 (1940) were sparse and had not raised a broad discussion over “min-jian vs. official.” Moreover, many animation works were made for commercial purposes or duty requests; the lack of non-profit cases and self-expression cases also shadows the “non-profit vs. commercial” paradigm. For example, Yang Zuotao 杨左匋 made two pieces of so-called “funny motion pictures” 活动滑稽画片, i.e. Pause 暂停 (1923-24) and Guo Nian 过年 (1923-24), for the movie department of the British American Tobacco Company 上海英美烟草公司影戏部; Huang Wennong 黄文农 made a namely “pen-and-ink motion picture” 活动钢笔画影片 Dogs Treat 狗请客 (1924) for the China Film Company 中华影片公司; and Qin Lifan 秦立凡 who acted as the art consultant for the Great China Baihe Company 大中华百合公司, made Ball Man 球人 (1924) – a work combined with animation skill and live action shot.[21]

On this basis, from the 1920s to the 1950s, the exploration of animation aesthetics and technology in China was still in a nascent stage, and had not reached a consistent style or technical maturity. As for the “personal creation vs. team production” paradigm, though we have personal/small-scale commissions created by Yang Zuotao, Huang Wennong and Qin Lifan, and the Wan Brothers’ large-scale production Princess Iron Fan 铁扇公主 (1941) that invested CNY 2 million and made with over 200 animators/workers, these cases are too weak to be regarded as “team production.”[22] Let alone, Princess Iron Fan was made by “dozens of apprentices who could not paint” 几十名不会绘画的练习生, as Wan Laiming 万籁鸣 and Wan Guohun 万国魂 recorded.[23]

As a result, though there was no such term for “independent animation” in China before the mid-late 1980s, previous practices had laid a foundation for the “min-jian vs. official” paradigm. In addition, even though scholars usually describe SAFS works (and those of ink-wash painting style, with paper-cut figures or with puppets in particular) as “experimental” ones, we argue that the “experimental vs. non-experimental” paradigm is mainly found in a contemporary art sphere, where “pioneering animations” 先锋动画 and “conceptual animations” 观念动画 are some similar terms. Notably, standing upon Zhang Peili 张培力’s contribution (esp. 30X30, 1988) to the boom of new media art in China, it was in the context of contemporary art (esp. 2012 Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale) that domestic scholars started to discuss independent animation in an academic discourse.[24]

Figure 3. The Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale was held in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2019. Here is the catalog of the fourth and last biennale so far. (Source Guo Baoyi, photo taken on August 23, 2025.)

From then on, the National Radio and Television Administration 广播电影电视部 issued Several Opinions of Deepening Reforms of the Mechanism of the Film Industry 关于当前深化电影行业机制改革的若干意见 in 1993, which marked the marketization of China’s film industry. In 1997, Flash entered China, subsequently raising the curtain of a “Shan-ke Era” 闪客时代. Later, contemporary art was legalized in China at the 2000 Shanghai Biennale. In 2001, the Central Academy of Fine Arts set up a “Digital Media Studio” 数码艺术工作室, where the school’s power showed up. Consequently, when China’s animation production, film-television industry and tertiary education interacted with each other at the beginning of the new century, what we are talking about “independent animation” was also generating a perspective discrepancy in aesthetic judgments.

Internet Empowerment: the Differentiation of “Low Culture vs. High Culture” and the Deepening of “Grassroots vs. School”

In our opinion, three clues interactively contribute to the perspective discrepancy in aesthetic judgments of China’s independent animation. Firstly, Flash, the software, became popular around 2000 and technologically empowered “grassroots” animation creators. Secondly, “flashempire.com” 闪客帝国, the largest domestic community website among Shan-ke from 1999 to 2009, became a main platform for distributing so-called “low culture” animations. Thirdly, artists from the contemporary art area have kept making independent animations, which further consolidates the public impression of “high culture” and “school.”

Admittedly, the rise and fall of flashempire.com should be our pivotal clue for studying China’s independent animation in the 2000s. To elaborate, from the year 1988 when Zhang Peili created 30X30, to the year 1997 when Flash entered China, although we had new media art including GIFs, slide films, interactive installations, and other animated works (e.g., Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy 智取威虎山, 1994; My Private Album 私人照相簿, 1996; The Journey of Mens and Lust 心欲之旅, 1999) (cf. Video Bureau 录像局), they had not been widely distributed beyond the art world nor on the Internet.[25] After flashempire.com was set up in 1999, due to the popularization of personal computers, the user-friendliness of Flash and the common use of Flash Player, amateur animation creators popped up, then profoundly influenced the domestic creative ecology until around 2010. However, technological empowerment does not directly lead to a perspective discrepancy in aesthetic judgments. After breaking off from the official assessment system for “short films” 艺术短片 or “short mei-shu film” 美术片小品 during the SAFS era, discussion over nascent Flash-made animations has involved more stakeholders – not only from audience and media, but also from academia and industry.[26]

In this Flash-dominated period, we suggest that both animations and their creators were described as “grassroots” in an early phase. As the word represents, everyone could access animation production, which is opposite to the state monopoly of animation-producing expendables. Meanwhile, “grassroots” as an adjective also indicates the creators’ educational background. Particularly, although art college graduates (e.g., Pi San 皮三, Bu Hua卜桦, Bai Ding 白丁 — aka Zhu Zhaoxi 朱兆曦) and their counterparts shared the same technical tools to make independent animations, and “arts.tom.com” 美术同盟, a professional community website for domestic artists, launched “Shan-ke forum” in 2001, those graduates have stayed in the art world, instead of adhering to the “grassroots” creators.[27]

Accordingly, Gudu Guoke 孤独过客 (aka Wang Wei 汪韡), a famous Shan-ke, categorized his peers into “Computer Geeks” 技术派 and “Artists” 艺术派. In his observation, as the “Computer Geeks” usually major in Computer Science, they are better at software programming than aesthetic expression; while the latter, art college students as representatives, are on the contrary.[28] Moreover, educational background has heavily influenced what the Shan-ke makes and where their career goes. Take some computer geeks as examples, Biancheng Langzi 边城浪子 (aka Gao Dayong 高大勇) – the founder of flashempire.com, Xiaoxiao 小小 (aka Zhu Zhiqiang 朱志强) – whose representative work is the Xiao Xiao Series 小小系列 (2000-2002), and BBQI (aka Qi Chaohui 齐朝晖) who made Love Song 1980 恋曲 1980 (2001), have all finally jumped into the game-production areas. In contrast, artists such as Bai Ding, Bu Hua and Lao Jiang 老蒋 (aka Jiang Jianqiu 蒋建秋) – whose representative work is Rock ‘n’ Roll on the New Long March 新长征路上的摇滚 (2000), have chosen to continue their animation production or to teach at art colleges.[29]

Figure 4. We can now still access some works made by Shan-ke via accessing the Flash Archive Project (https://flash.zczc.cz/). (Screenshot taken on August 23, 2025.)

Furthermore, influenced by the development of new media art in China, prestigious art colleges also began to set up relevant majors and departments. To illustrate, following the Digital Art Studio of the Central Academy of Fine Arts set in 2001, the China Academy of Art founded a New Media Department 新媒体艺术系 in 2003. Then, in 2004, the Beijing Film Academy established the New Media Laboratory 新媒体实验室.

Thus far, the “grassroots vs. school” paradigm had begun to take shape, but it was seldom highlighted due to its limited influence. On the contrary, from a perspective of aesthetic appreciation, the “low culture vs. high culture” paradigm has been widely applied in mainstream criticism.

For one thing, when negative comments towards Shan-ke became common (e.g., weird, devoid of beauty, needs professional design), a work named Adults Only 少儿不宜 (2000) was criticized as a vulgar and erotic production. Responding to this controversy, Bai Ding, the author of Adults Only, later created a more philosophic Lost Dream 失落的梦境 (2003). At the same time, with most flash animations becoming similar and dull, these kinds of works had gradually been linked to “low culture” as well. As a result, “low culture” has reflected some stereotypes, regarding not only the animations themselves (e.g., superficial themes, low-cost productions, and overhyped stories), but also some creators’ amateur backgrounds. For the other thing, after Bu Hua released her work Cat 猫 (2002), the descriptor “high culture” has been widely recognized, making animations made by the “Artists” more acclaimed.[30] This trend was further exemplified via the news reports that Cat was short-listed in the 2004 Annecy International Animated Film Festival and the 2006 Zagreb World Festival of Animated Film – two renowned events for showcasing animated shorts. Besides, as the number of art exhibitions focusing on independent animation increased and Internet activities featuring User Generated Content arose (e.g., Tudou Film Festival 土豆映像节) in the late 2000s, we observed a wider aesthetic discrepancy towards personally created animations. Consequently, the “low culture vs. high culture” paradigm has been strongly affirmed.

Among these exhibitions, by highlighting the kinship between exhibits and contemporary art through film selection and promotion, the 2008-2009 Beijing Independent Film Festival 北京独立影像论坛/独立电影展, and the 2009 Post 24 Independent Animation Festival 后24独立动画展 in Shanghai have made a great contribution to disseminating the academic usage of “independent animation.” In addition, from 2008 to 2015, the Tudou Film Festival emphasized the grassroots and non-academic attributes of its participants by giving prizes to works such as See Through 打,打个大西瓜 (2008), Lee’s Adventures 李献计历险记 (2009), I’m MT 我叫MT (2009), and The Red 红领巾侠 (2010).

Therefore, around 2010, the “low culture vs. high culture” paradigm for showing audiences’ appreciation preference was differentiated, and the “grassroots vs. school” paradigm for labeling creators’ education or career background was deepened. These phenomena could be reflected in both submission inquiries and short-listed results of the aforementioned exhibitions/festivals.

Even so, “low culture vs. high culture” and “grassroots vs. school” do not fully represent the picture and legacy of “flashempire.com”. From an animation production perspective, it is significant that industrialized attempts at Flash animation and Shan-ke have strongly accelerated the marketization process of Chinese animation. Along these lines, cases of Shan-ke adhering to commercial activities (e.g., Hutoon 互象动画, B&T彼岸天, ITS Cartoon歪马秀/其卡通, L2 Studio 中华轩/艾尔平方, and Busifan 悠无一品/不思凡) are worth researching.

Business Environment: Strengthening “Non-profit vs. Commercial” and Labelling “Personal Creation vs. Team Production”

As a major driving force, the commercialization of Flash animation and Shan-ke has closely fueled the industrialization of Chinese animation. But take the year 2015, when Monkey King: Hero Is Back 西游记之大圣归来 became an unprecedented success as a turning point, the business environment surrounding independent animation in China has been refreshed, where the word “independence” newly refers to personal creation and non-profit works.

Admittedly, without the investment and distribution support from large-scale filmmaking studios, personally-created or small team-produced animations usually have less potential to make a profit than the commercial ones. However, we suppose that the association between independent animation and its “non-profit” feature in China, as well as its opposition to commercial animation in the public perception, has not existed from the very beginning.

“Non-profit” 非盈利 in Chinese, means “unprofitable” or “not for profit.” Then, when people talk about “unprofitable,” they usually refer to a business entity that is running at a loss. In this sense, although some animation companies choose to make profits by undertaking outsourcing projects or applying for subsidies from the government, most of their fellows have suffered to make ends meet via a mere primary income (excl. secondary income from selling DVDs, merchandise and copyright). Particularly, from 2000 to the early 2010s, both web animations and animated features were at their doldrums; thus, a public image that “making animations cannot make money” has been subtly generated.

For instance, domestic television stations usually paid no more than CNY 500 to 600 per minute to the TV animation producers, which was too little to offset the enormous cost.[31] As to web animations, monetization trials such as ad placement, membership plan and copyright licensing for the streaming platforms and their content providers were nascent and imperfect. Hutoon, producer of the so-called “first Chinese animated online TV show” Miss Puff 泡芙小姐 (2010), even sued Youku over default payments.[32] In terms of animated films, when SAFS’s Lotus Lantern 宝莲灯 gained “a great success” with CNY 12 million cost, CNY 25 million total gross and over 3 million audience in 1999,[33] works released several years later, such as Thru The Moebius Strip 魔比斯环 (2005, CNY 3.6 million total gross), Saving Mother 西岳奇童 (2006, CNY 4 million total gross), Sparking Red Star 闪闪的红星 (2007, CNY 5 million total gross) and Calabash Brothers 葫芦兄弟 (2008, CNY 8.5 million total gross), subsequently flopped. Notably, although Storm Rider: Clash of Evils 风云决 broke the box office record of Lotus Lantern in 2008 with CNY 27 million, compared with its cost (CNY 60 million, a five-year production), the film is regarded as an investment tragedy in the history of Chinese animation.[34]

It was not until Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf 喜羊羊与灰太狼之牛气冲天 and One Hundred Thousand Bad Jokes 十万个冷笑话 became blockbusters that the situation was rectified. Adapted from a preschool animated TV series, the first Pleasant Goat and Big Big Wolf movie was released in cinemas in 2009. Then, by taking over CNY 100 million total gross, it has become a milestone in the history of Chinese animated features. Later, One Hundred Thousand Bad Jokes was released online and became a great hit with over 100 million clicks in China.[35] Therefore, when this animation brand released its first movie in 2014, it took over CNY 100 million total gross, becoming an unprecedented feat of a non-children-oriented Chinese animated feature. Unfortunately, there were few successful cases, let alone those works made by individuals or small teams. For example, Piercing I 刺痛我 (2010), an animated feature independently made by Liu Jian 刘健, could only be distributed online.[36] Before Monkey King: Hero Is Back (CNY 954 million total gross) broke a new box office record in 2015, high-cost original animated feature such as The Legend of Qin 秦时明月之龙腾万里 (2013, CNY 59 million total gross), Dragon Nest: Warriors’ Dawn 龙之谷:破晓奇兵 (2014, CNY 57 million total gross), 10000 Years Later 一万年以后 (2014, CNY 27 million total gross) and Kuiba 魁拔 series (2011-2014, CNY 54 million total gross for three films), subsequently failed.

As such, even with the team efforts, it is not easy for commercial animations to make profits, not to mention those independent works. In this light, when people talk about domestic animations in a wider public space, it has been inevitable to describe them as commercial projects, unprofitable pieces, personal creations or team productions.

However, according to our research on the dynamics of domestic personal creators, we argue that some of their key opinion leaders have kept identifying themselves as “independent animators” 独立动画人. As a result, they have also strongly underlined the “not-for-profit” attribute of China’s independent animations.

Specifically speaking, firstly, as the concept of “independent animation” was widely disseminated in the 2000s, both differences and connections between independent and commercial animations have become a common topic and agenda for relevant exhibitions/festivals. And such practices have been inherited by the Feinaki Beijing Animation Week,[37] an independent animation-focused event founded in 2019.

Secondly, though some typical representatives among independent animators do not resist commercial projects, they normally distance themselves from “mainstream” or “commercial” animations, especially when it comes to their living environment and status. Thirdly, they also often express their discontent with controversial monetization behaviors such as subsidy deception, childish work and low-quality production;[38] thus, enlarging the gap between independent and commercial animations to some extent.

Thereby, when those “not-for-profit” independent animators set the tone for an unprofitable market environment among public opinions, against the scenario that the animation industry has been increasingly industrialized and commercialized in China, gaps and stereotypes between independent and commercial animations have also been elevated. In addition, besides Shan-ke, other kinds of personal creators have been incorporated into the commercial system. The so-called “Web animators” Web 系原画师 represented by Guangxue Hexin 光学核心, i.e., people who make use of online materials and teach themselves animation-making knowledge, are pointed out. Meanwhile, when the commercial value of Chinese animations has been gradually pulled up by industrialized works (e.g., the productions of Coloroom 光线彩条屋 and Light Chaser Animation 追光动画), the advantages of industrial production are further shown, leading to a stickier label of “personal creation vs. team production.”

These label reinforcements are threefold. Firstly, when successful stories of personal creations being shifted to team productions gain more attention, similar choices become more acceptable. Particularly, around 2015, as domestic animation companies received more funds or investments, personal studios and small teams such as Cococartoon 可可豆 (Ne Zha series 哪吒之魔童降世/闹海, 2019/2025), One&All Animation Studio 中传合道 (Legend of Deification 姜子牙, 2020) and HMCH 寒木春华 (The Legend of Luoxiaohei series罗小黑战记系列, 2019/2025) began to seek a higher production capacity for making an animated feature. Some of them even outsourced and accepted foreign collaborations, which was nearly unattainable in the past scenarios. Secondly, when the number of animated blockbusters increased and the competition among streaming platforms intensified, domestic competitors including Tencent Video, Bilibili and Youku began to launch projects that support young animation directors. As a result, they accelerate the expansion process of many personal or small-scale studios in China. Thirdly, though current discursive foci of China’s animation industry still dwell on an old-fashioned argument swaying between either a director-centered or a producer-centered system,[39] the industry in practice has kept calling for releasing more voices to animation producers. Compared to the film industry’s long-lasting advocacies on standardizing the responsibilities of producers, developing the management mindset for directors, and enhancing their work efficiency, the focus on the production perspective of the animation industry is relatively outdated.[40]

Overall, we argue that it was not until 2015 that independent animations in China were regarded as non-profit personal creations, due to significant changes in the business environment for the domestic animation industry. Nevertheless, outlier cases such as Liu Jian and “FIRST directors” as a collective exist, as those independent creators usually make their debuts at the FIRST International Film Festival.[41] Liu Jian’s latest Art College 1994 made its Chinese premiere at the 17th FIRST in 2023; it was also the first time that FIRST chose an animated feature as the opening film. With nascent works titled “Short Animation Collection” 动画短片集 (e.g., the intervals of Black Myth: Wukong) and animated features/series incubated from their short counterparts (e.g., Fog Hill of Five Elements 雾山五行, 2016-2023; Nobody 浪浪山小妖怪, 2025), we are now witnessing how works that used to be non-profit and personally created are earning greater possibilities in China. This, plus generative AI that is turning more upskilled users into animation creators, continuously challenges production forms and people’s thoughts on “independent animation” as an umbrella term.

Figure 5. As a preview or warm-up before Art College 1994 was formally released in China on June 21, 2025, the film had limited screenings overseas. Here is its introduction from the flyer for the “Modern China Film Festival” 現代中国映画祭 held in Japan in 2024. This film ultimately grossed CNY 0.728 million at the Chinese box office. (Source Guo Baoyi, photo taken on September 1, 2025.)

Conclusions, Limitations and Implications

To summarize, as a medium that can be made and appreciated by both general and professional creators, in domestic research and discussion, animation has long shown its differences (rather than opposition) between the aesthetics and the production aspects.[42] However, when the term “independence” has been mixed up in the fields of animation, film and contemporary art, its definition becomes vague and makes people confused.

In response, based on an animation-film-contemporary art intertwined perspective, this paper attempts to sort out the complicated relationships among (1) min-jian vs. official, (2) grassroots vs. school, (3) low culture vs. high culture, (4) experimental vs. non-experimental, (5) non-profit vs. commercial, and (6) personal creation vs. team production. On this basis, this paper also clarifies what “independence” could mean in reference to China’s independent animations. Among these paradigms, we argue that there are at least three characteristics to describe an independently-made animation work in the Chinese context, i.e., min-jian, non-profit and personal creation. Specifically, they reflect both emphases and changes for the “independence” of domestic independent animations from a production perspective, ranging from the periods of 20th-century SAFS, the 2000s rise and fall of “flashempire.com,” and the post-2010s development of the animation industry.

Despite research outcomes, as the study of China’s independent animation is far from a mature stage and most of its relevant discussions are relatively subjective, limitations are flagged up. For one thing, compared to Zhan and Yin’s empirical research on the judgment of domestic independent films, documentaries, experimental images and video installations as a whole, i.e., made by an unemployed entity, invested by an unofficial channel, and filmed/released in an illegal way, this paper merely looks into the literature of producing independent animations, has not further investigated their financial sources and distribution channels.[43] For another thing, this paper has also not researched some occasionally-used descriptors such as “自主动画” and “自主制作”, as we treat them as loanwords from English (self-producing) or Japanese (自主制作アニメ).

More importantly, with controversy aroused by creators and scholars, the relationship between independent animations and independent films has been under debate in China.[44] Then being limited to various animation creation ecologies among countries/regions worldwide, foreign research not only less emphasizes its min-jian (unofficial) or official attribute, but also less compares and distinguishes its aesthetic or production aspect.[45]

In conclusion, as the authors agree and experience, making an artwork independently does not merely rely on some sort of spirit, but also involves a structured approach in everyday practices,[46] this paper attempts to clarify the Chinese meanings and references of independent animation’s “independence” from a production perspective. To further emphasize, despite the comprehensive study across animation, film and contemporary art areas, we do not suggest an equivocal mindset or equivalent theory among animation, live-action film, independent animation, and independent video. And though there are quite a few research perspectives and discourses that distinguish animated works by duration (making short films is often easier to achieve a “min-jian, non-profit, personal creation” status than producing the long ones),[47] we still maintain our focus on the production subject – the person – to consider how “independent animation” takes shape. As we can often observe individuals wearing multiple hats in the credits of independent animations, the “person” here, whether director, producer, animator or other roles, is equally worth exploring.[48] Thereupon, future studies are suggested to collect more primary resources and conduct an empirical analysis of the credit lists and the distribution channels of independent animation in China. To this end, we have already made an attempt at analyzing the prized and nominated lists of animated works spanning 2013-2023’s FIRST International Film Festival.[49]

Notes and Acknowledgments

This paper was first presented in Chinese at the “2022 Animation and Digital Arts International Conference”, organized by the Communication University of China. As a supplementary resource, the original bilingual slides can be accessed here. The authors later translated the paper into English with constant revisions and updates during 2023-2025. Additionally, the authors would like to express their gratitude to Mr. Fu Guangchao for his valuable insights, particularly on the history of the Shanghai Animation Film Studio.

[1] See Wei Wei 魏威, “Zhongguo dulidonghua lilunfazhan tanjiu – Jiyu CiteSpace de keshihua julei tupu fenxi 中国独立动画理论发展探究——基于 CiteSpace 的可视化聚类图谱分析 (Research on the development of China’s independent animation theory – visual clustering graph analysis based on CiteSpace),” Xiandai Xinxi Keji 现代信息科技 (Modern Information Technology) 6, 18 (2022): 89-95.

[2] Zhang Xiaotao 张小涛, “Beizhebide shiyan – 2000nian yilai zhongguo dulidonghua de shiyan zhilv 被遮蔽的实验——2000年以来中国独立动画的实验之旅 (The obscured experiment – the experimental journey of Chinese independent animation since 2000),” Yishu Pinglun 艺术评论 (Arts Criticism) 111, 2 (2013): 74-80.

[3] Anonymous, “Shenzhen dulidonghua shuangnianzhan baogao zhier: Shei wei zhongguo dulidonghua maidan? 深圳独立动画双年展报告之二:谁为中国独立动画买单? (Report of Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale No.2: who pays for Chinese independent animation?),” Yachang Yishu Wang 雅昌艺术网 (Artron.Net), 2012.

[4] “Contemporary animation” would be another term that is worth deliberately examining. For example, Yamamura Koji 山村浩二 categorized “independent animation in China” 中国独立系 as the localized practice of contemporary animationコンテンポラリー・アニメーション in a context that specifically refers to Mainland China, where Chen Lianhua 陈莲华 and Lei Lei 雷磊 are considered key figures. In Cao’s curation, independent animation is denoted as “animated work made based on individual production” 一个人的动画 in a converged context of contemporary art and animated art. Anonymous, “Xinzhan yugao | Xin zhongguoxuepai donghua nianwunian dazhan 新展预告|新“中国学派”动画廿五年大展 (Notice of new exhibition | 25th anniversary exhibition of the New Chinese School).” BEING Art Museum 浦东碧云美术馆, July 9, 2025.

[5] Dong Bingfeng, “The Ghost Goes West: Four Notes on the Themed Exhibition of 2nd Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennial,” in Vision and Beyond: 2nd Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale, ed. Dong Bingfeng and He Jinfang (Heidelberg: Alte Brücke Verlag, 2014), 16-21.

[6] Wei Shilei 卫诗磊, “Donghua gerenhua shidai de lailin – Zhongguo dulidonghua xianxiang yanjiu 动画个人化时代的来临——中国独立动画现象研究 (The advent of personal animation industry: research on phenomena of independent animation in China),” Zhuangshi 装饰 277, 5 (2016): 68-69.

[7] Chen Lianhua 陈莲华, Yiye yulongwu: Donghua lieguo youji 一夜鱼龙舞:动画列国游记 (Dance of Fish and Dragon – A Trip with Animation) (Beijing: Communication University of China Press, 2016), 162-163.

[8] Sha Dan 沙丹, Duan Tianran 段天然 and Zhu Yantong 朱彦潼, “Donghua jiezhan guancha 动画节展观察 (A conversation about animation film festivals and exhibitions),” Dangdai donghua 当代动画 (Contemporary Animation) 304, 4 (2023): 9-18.

[9] Zheng Yuming 郑玉明 and Yu Haiyan 于海燕, Donghua zhipian guanli 动画制片管理 (Animation Production Management) (Beijing: Communication University of China Press, 2015), 2-6.

[10] Wang Keyue 王可越, “Zhongguo dulidonghua: Hunzahua xingtai yu quanqiuhua xiangxiang 中国独立动画:混杂化形态与全球化想象 (Chinese independent animation: hybridized forms and global imagination),” Dianying yishu 电影艺术 (Film Art) 359, 6 (2014): 22-27.

[11] Xue Yanping 薛燕平, Feizhuliu donghua dianying 非主流动画电影 (Un-mainstream Animated Film III) (Beijing: Communication University of China Press, 2018), 303-326.

[12] Li Sixiao 李思潇, “Jiyu yu kunjing: Zhongguo dulidonghuaren shengtai yu zuopin xinxing tuiguang fangshi tanxi 机遇与困境:中国独立动画人生态与作品新型推广方式探析 (Opportunity and dilemma: exploring the ecology of Chinese independent animators and new promotion methods of their works),” (Master’s thesis, Fudan University, 2012). Zhou Wenhai, Chinese Independent Animation: Renegotiating Identity in Modern China (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 1-15.

[13] Zhang Yipin 张一品, “Zuozhe donghua – Zhongguo dangdaidonghua de yishu shiyan 作者动画——中国当代动画的艺术实验 (Author animation – the contemporary animated art experiment),” (PhD dissertation, China Academy of Art, 2015).

[14] For animated works in China, it ended in January 1995, when the Chinese government abolished the system of purchasing animation works from state-owned animation studios.

[15] Han Peng 韩鹏, “Jingdian de jiazhi yu chanshi – Zailun zhuanxingqian de zhongguo donghuadianying 经典的价值与阐释——再论转型前的中国动画电影 (The values and interpretations of classics: Chinese animated films before the transformation in 1980),” Dangdai dianying 当代电影 (Contemporary Cinema) 246, 9 (2016): 182-185.

[16] Liu Shuliang 刘书亮, “Zhongguodonghuaxuepai de gainian kaoyuan, zaoqichuanbo yu dangdaiyanzhan” “中国动画学派”的概念考源、早期传播与当代延展 (The conceptual genealogy, early dissemination and contemporary extension of Chinese Animation School), Xiandai chuanbo 现代传播 (Modern Communication) 323, 6 (2023): 108-114.

[17] Cao Kai 曹恺, “Yiluo zhi feng: yibu shiyandonghua de qianbiaoceng fajue 遗落之“风”:一部实验动画的浅表层发掘 (The ‘Wind’ of the fall: the shallow surface excavation of an experimental animation),” Huakan 画刊 (Art Monthly) 465, 9 (2019): 71-75.

[18] Fu Guangchao 傅广超, “Liangjie erzhong: zhongguo guoji donghua dianyingjie chenfulu 两届而终:上海国际动画电影节浮沉录 (The end of two festivals: rise and fall of Shanghai International Animation Film Festival),” Duku2302 读库 2302 (Beijing: New Star Press, 2023), 45-155.

[19] Wu Weihua, “The ambivalent image factory: the genealogy and visual history of Chinese Independent Animation,” Animation 13, 3 (2018): 221-237.

[20] Cao Kai 曹恺, “Fushi jiagou – Zhongguo duli dianying shishu moxing 复式架构──中国独立电影史述模型 (Compound structure – A model of Chinese independent film history),” Xiju yu yingshi pinglun 戏剧与影视评论 (Stage and Screen Reviews) 12, 3 (2016): 13-21.

[21] Yin Fujun 殷福军, “Shoupi zhongguo donghuapian ji zuozhe de kaozheng 首批中国动画片及作者的考证 (Textual research on the first Chinese animated films and their authors),” Dianying yishu 电影艺术 (Film Art) 312, 1 (2007): 146-150.

[22] Fu Guangchao 傅广超, “Zhongguo donghua changpian chuangshiji: wanshi xiongdi de tieshangongzhu gongzuo baogao | lishi gouchen 中国动画长片创世纪:万氏兄弟的《铁扇公主》工作报告|史料钩沉 (The genesis of Chinese Animated Feature Films: a work report of the Wan Brothers’ Princess Iron Fan | Past Stories),” Kongzang Dongman Ziliaoguan 空藏动漫资料馆 (Kongzang Animation & Comics Archive), November 19, 2021.

[23] Wan Laiming 万籁鸣 and Wan Guohun 万国魂, Wo yu songwukong 我与孙悟空 (The Monkey King and I) (Taiyuan: Beiyue Wenyi Chubanshe, 1986), 88.

[24] Wang Chunchen, “The World of Soul: Building Virtual Art Engineering – On the Theoretical Significance of Chinese Independent Animation,” in Documents of the First Shenzhen Independent Animation Biennale, ed. Wang Chunchen, Zhang Xiaotao and He Jinfang (Beijing: China Youth Publishing Group, 2012), 11-13.

[25] Qiu Zhijie 邱志杰 and Wu Meichun 吴美纯, “Zhongguo luxiang yishu de xingqi yu fazhan 1990-1996 中国录像艺术的兴起与发展 1990-1996 (The emergence and development of video art in China 1990-1996),” in Feixianxing Xushi 非线性叙事 (Non-Linear Narrative), ed. Wu Meichun and Xu Jiang (Hangzhou: China Academy of Art Press, 2003).

[26] Jin Xi 靳夕, “Gaoxie meishu xiaopin 搞些美术片小品 (Create Some Short Mei-shu Films),” in Meishu Dianying Chuangzuo Yanjiu 美术电影创作研究 (Research on Mei-shu film creation), ed. Dianying Tongxun Bianjishi《电影通讯》编辑室 (Editorial Committee of Dianying Tongxun) (Beijing: China Film Press, 1984), 76-79.

[27] Qiu Zhijie 邱志杰 and Wu Meichun 吴美纯, “Xinmeiti yishu de chengshou he zouxiang 1997-2001 新媒体艺术的成熟和走向1997-2001 (The maturity and direction of new media art 1997-2001),” in Feixianxing Xushi 非线性叙事 (Non-Linear Narrative), ed. Wu Meichun and Xu Jiang (Hangzhou: China Academy of Art Press, 2003).

[28] Biancheng Langzi 边城浪子, Shanke diguo jinghuaji 1 闪客帝国精华集1 (Collection of Flash.Empire 1) (Beijing: Publishing House of Electronics Industry, 2003), 356.

[29] Jiuyue 九月, “Wei meiyou lishi de hulianwang liuxia lishi – Shanke diguo huiyilu 为没有历史的互联网留下历史——闪客帝国回忆录 (Remarking history for the Internet without history – memoirs of the Flashempire.com),” Youxi Yanjiu She 游戏研究社 (Game Research Society), August 4, 2017.

[30] Wang Bo 王波, “Flash zai zhongguo Flash 在中国 (Flash in China),” In Flash: Jishu haishi Yishu Flash:技术还是艺术 (Flash: Technology or Art) (Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2005), 17-71.

[31] Qian Jianping 钱建平, Shi Chuan 石川 and Geng Shuai 耿帅, “Guochan donghuapian de zuotian, jintian he mingtian – Qian Jianping fangtan lu shang 国产动画片的昨天、今天和明天——钱建平访谈录上 (Yesterday, today and tomorrow of domestic animated films – interview with Qian Jianping Part I),” Dangdai Donghua 当代动画 (Contemporary Animation) 298, 2 (2022): 34-40.

[32] Pi San皮三, “Wangluo donghua 3.0 shidai 网络动画3.0时代 (The 3.0 period of web animation),” Zhongguo Dianshi – Donghua 中国电视(动画)(China TV – Animation) 51-52, Z1 (2014): 10-15.

[33] Dongfang rizhi – Shanghai gushi 东方日志—上海故事 (Lock Today: Shanghai Story), aired July 30, 2008 on Dongfang Weishi 东方卫视 (Dragon TV).

[34] Considering the opacity and time-related discrepancies in early domestic film cost and box office data, this paper references official media reports for data up to 2010. For data from 2011 onward, it incorporates a comprehensive review of sources, including online media reports, company financial statements if available, Maoyan Pro, and Lighthouse Pro.

[35] Wu Xuguang 吴旭光, “Shiwange lengxiaohua daihuo dongman ziben, Youyaoqi chenre shengeng IP chanye 十万个冷笑话带火动漫资本,有妖气趁热深耕IP产业 (One Hundred Thousand Bad Jokes fueled the animation industry, as U17 Comics capitalized on the success to further develop its IP industry),” Lichai Zhoubao 理财周报 (Money Week), April 26, 2015.

[36] Liu Jian 刘健, “Geren donghua gongzuoshi de chulu: citongwo yu wangluo faxing 个人动画工作室的出路:《刺痛我》与网络发行 (The prospects of individual animation studios: Piercing I and online distribution),” Zhongguo Dianshi – Donghua 中国电视(动画)(China TV – Animation) 38, 1 (2013): 31.

[37] Zhu Yantong 朱彦潼, “Duitan huigu: cong huiben dao donghua, cong duli donghua dao yuanxian donghua dianying | feinaqi x benlai yingye 对谈回顾:从绘本到动画, 从独立动画到院线动画电影 | 费那奇X本来影业 (Conversation Review: From Picture Book to Animation, From Independent Animation to Theatrical Animated Feature | Feinaki X Benlai Pictures),” Feinaqi Donghua Xiaozu 费那奇动画小组 (Feinaki Animation Group), January 16, 2021.

[38] Song Lei 宋磊, “Zhongguo duli donghuaren de shengcun xianzhuang 中国独立动画人的生存现状 (The living status of Chinese independent animation creators),” Wenhua Yuekan·Dongman Youxi 文化月刊·动漫游戏 (Cultural Monthly·ACG Review), 6 (2011).

[39] Qian Jianping 钱建平, Shi Chuan 石川 and Geng Shuai 耿帅, “Guochan donghuapian de zuotian, jintian he mingtian – Qian Jianping fangtan lu xia 国产动画片的昨天、今天和明天——钱建平访谈录下 (Yesterday, today and tomorrow of domestic animated films – Interview with Qian Jianping Part 2),” Dangdai Donghua 当代动画 (Contemporary Animation) 299, 3 (2022): 58-63.

[40] Zhang Yu 张煜, “Zhongguo dianying zhipianren jizhi de xianzhuang yu biange 中国电影制片人机制的现状与变革 (The situation and change of China film producer system),” Dangdai Dianying 当代电影 (Contemporary Cinema) 214, 1 (2014): 4-20.

[41] Zhang Xiaoming 张晓铭, “Zouxiang dazhong: FIRST xi daoyan chutan 走向大众:“FIRST系”导演初探 (Towards the public: a first Look at the FIRST directors),” Dianying Wenxue 电影文学 (Movie Literature) 734, 17 (2019): 97-101.

[42] Zhang Songlin 张松林, “Mantan zhongguo donghuapian de qiantu 漫谈中国动画片的前途 (Talk about the future of China animation).” Zhongguo Dianshi 中国电视 (China Television), 12 (1992), 35-37.

[43] Zhan Qingsheng 詹庆生 and Yin Hong 尹鸿, “Zhongguo duli yingxiang fazhan beiwanglu 1999-2006 中国独立影像发展备忘录1999-2006 (Memorandum on the development of independent video in China 1999-2006),” Wenyi Zhengming 文艺争鸣, 5 (2007): 100-127.

[44] Pi San皮三, “Zhongguo duli donghua shinian yipie 中国独立动画十年一瞥 (A decade of independent animation in China at a glance).” Huakan 画刊 (Art Monthly) 375, 3 (2012): 64-66. Zhao Yiping 赵毅平 and Jia Shan 贾珊, “Tuxiang, jiyi yu shiyan – Lei Lei de donghuayingxiang chuangzuo 图像、记忆与实验——雷磊的动画影像创作 (Image, memory and experiment – Lei Lei’s animation and movie image creation),” Zhuangshi 装饰333, 1 (2021): 76-81.

[45] See the American experience and the Japanese insight. Ben Mitchell, “Introduction,” in Independent Animation: Developing, Producing and Distributing Your Animated Films (Boca Raton: CRC Press of Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 1-10. Doki Nobuaki 土居伸彰, 21 Seiki no Animēshon ga Wakaru Hon 21世紀のアニメーションがわかる本 (The Book of Understanding Animation in the 21st Century) (Tokyo: FilmArt, 2017), 9.

[46] Xiang Biao and Wu Qi, Self as Method: Thinking Through China and the World, trans. David Ownby (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 232-233.

[47] Chen Liaoyu 陈廖宇, Yu Shui 於水, Chen Lianhua 陈莲华, Jiang Shen 姜申 and Liu Mengya 刘梦雅, “Zhongguo qitan chuangzuotan《中国奇谭》创作谈 (The conversation about the creation of Yao-Chinese Folktales),” Dangdai Donghua 当代动画 (Contemporary Animation) 302, 2 (2023): 6-18.

[48] Dai Lu 戴璐, “Donghua dianying de zuozhe wenti chuyi 动画电影的‘作者’问题刍议 (On my discussion about the Author of animation film),” Sichuan Xiju 四川戏剧 (Sichuan Drama), 4 (2024): 80-83.

[49] Bifang 彼方 and Baoyi, “Qu zhongguo zuiye dianyingjie kan donghua, shiyizhong shenme tiyan 去「中国最野电影节」看动画,是一种什么体验 (What was the experience of watching animation in the wildest film festival in China)”, Donghua Xueshupa 动画学术趴 (Anim-Babblers), October 12, 2023.

BIO:

Wang Yang is a writer and was the Editor-in-Chief of “Anim-babblers (Donghua Xueshupa)” (2020-2025), an SNS-based industry media that specializes in offering news, reviews and academic dynamics for professional animators and animation fans in the Chinese context. He also acted as a preliminary juror of The 6th Feinaki Beijing Animation Week (2024).

Guo Baoyi is a contributing writer of “Anim-babblers” (2021-present). As both a researcher and practitioner in the film and animation industry, her research field mainly lies in popular culture and the cultural/creative industry in East Asia. She is currently undertaking a long-term art-based research/research-based art project on “Cantonese Animation” (2024-ongoing).