By Grace Han

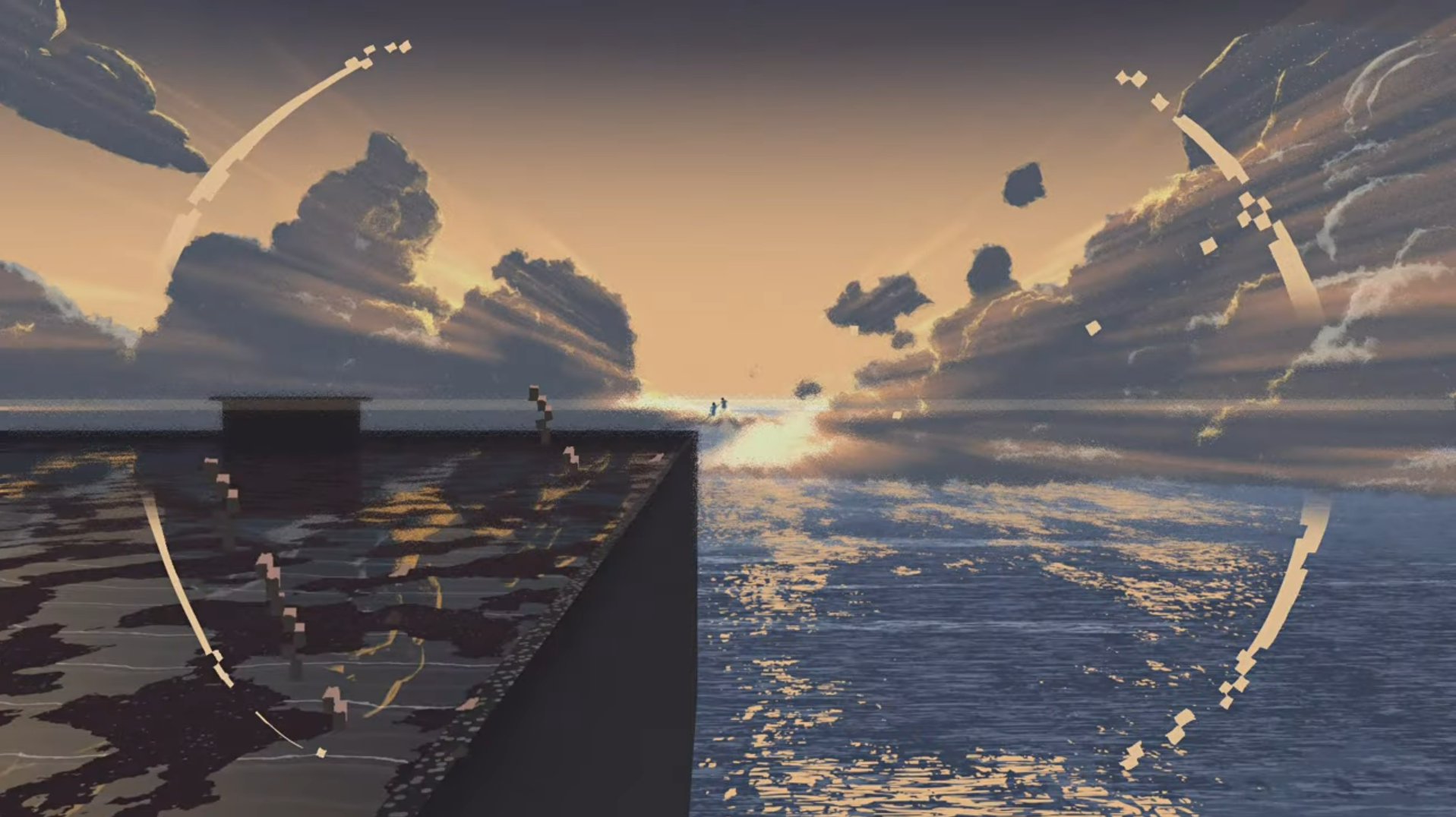

The hour strikes; the lights dim. The gentle call of ocean waves washes over the audience. The 4-note singsong of the school bell rings in the distance. Then, suddenly, a girl, soaked in pastel azure blues, appears on-screen. We follow her rotoscoped form closely, climbing up the stairs to the school rooftop with her. As she opens the door, we spot another girl, clad in school uniform, looking out towards the cerulean seas on the rain-soaked terrace. The schoolgirl leaps over the rooftop’s edge, as does our protagonist from the stairs. Their hands touch, their eyes meet, and – in this extreme long shot – the camera takes a step back (fig 1). The film pauses. As the two remain suspended between the heavens and the earth, silhouetted by a majestic lens flare over the horizon, a voiceover ponders aloud in Korean: “Where are we going? What will we become?”

Fig 1: Two figures framed in the 19th Seoul Indie-Anifest trailer (2023), by Han Ji-won.

Fig 1: Two figures framed in the 19th Seoul Indie-Anifest trailer (2023), by Han Ji-won.

These questions seemed to weigh upon the 19th iteration of the Seoul Indie-Anifest, in addition to this festival trailer by Han Ji-won. At the packed opening ceremony, festival director Yujin Choi revealed that the slogan for the festival this year was “Nineteen,” in reflection of the festival’s own coming-of-age. After all, in South Korea, age 19 just precedes the legal age of 20; as such, 19 marks the turning point of adolescence. Moreover, Choi remarked that this year witnessed the festival’s first full-blown return from the COVID-19 pandemic. While the festival operated in-person for the last three years, it did so at reduced capacity. In contrast, the festival completely opened its doors this year at CGV Yeonnam, ushering in international guests and the public alike (fig 2).

Fig 2: A view from Indie-Ani Night, an evening celebration midway through the festival. Photo courtesy of Indie-Anifest.

Fig 2: A view from Indie-Ani Night, an evening celebration midway through the festival. Photo courtesy of Indie-Anifest.

The ghost of the immediate pandemic makes it feel particularly fitting to write this report for the Association for Chinese Animation Studies. Chinese presence in the Korean animation scene has changed considerably since the last report on this site. Previously, Daisy Yan Du wrote about (and coincidentally, also the 19th iteration of the) Seoul International Cartoon and Animation Festival (SICAF) in 2015, which featured China as its guest of honor. Here, according to Du, SICAF spent time on retrospectives from Shanghai Animation Studio. Now, eight years later, SICAF has folded; its last edition was in 2021. The Seoul Animation Center in Namsan began renovations, temporarily removing Indie-Anifest from its original home at the CGV Myeong-dong. And now, amid the hustle and bustle of the hip Hongdae, Indie-Anifest seemed to explode with more activity than ever. The opening ceremony reception (suitably, at a K-BBQ restaurant) buzzed with young and cutting-edge filmmakers, including students and industry insiders alike (fig 3).

Fig 3: Seoul Indie-Anifest opening reception. Photo courtesy of Indie-Anifest.

Fig 3: Seoul Indie-Anifest opening reception. Photo courtesy of Indie-Anifest.

Moreover, in contrast with SICAF’s concerted effort to focus on Chinese animation, Indie-Anifest seemed to stumble into the world of Sinophone selections by coincidence. In Asia Road, the festival’s pan-Asian shorts competition, at least 19 out of 34 shortlisted films (55%!) featured works from directors based in Sinophone areas or are of Chinese descent (China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore). This is nearly double from the previous year, where only 10 out of 34 films — and some of them international collaborations — featured contributors of Chinese descent.

It would be difficult and misleading to simply label these works as “Chinese animations” and call it a day, however. Unlike the state-sponsored Shanghai Animation Studio of the 20th century, these independent animated shorts have little to do with the state or sometimes, ethnic identity. Perhaps this had to do with the fact that many independent shorts seemed to receive funds from corporate platforms. For instance, the Prize for Asia Road-winner CHACHA (2022), received sponsorship from Billibilli Capsule (fig 4). The viewing platform’s sponsorship seems to have stretched the geographic scope of the content on-screen, as in the case of Paris-based directors Shang Zhang and Chenghua Yang. As if reflecting their own diasporic experience, they crafted a short mixing digital animation and Cezanne-esque watercolors about two middle-aged, Chinese couples road-tripping through the French countryside for their children’s wedding.

Fig 4: A still from CHACHA (2022) by Shang Zhang and Chenghua Yang.

Fig 4: A still from CHACHA (2022) by Shang Zhang and Chenghua Yang.

It seemed to me that CHACHA — though a Mandarin-language film — wanted to appeal to a universal sentiment about parenthood. Viddsee-sponsored Tangle Lah! (2022) also seemed to beckon towards a common experience of neighborly goodwill. Here, in this apartment complex, a young Chinese couple’s laundry pole becomes entangled with their Malay and Indian neighbors’ laundry. In the Q&A, director Qing Sheng Ang noted that he wanted to push against ideas of a Sinocentric Singapore. As such, Qing Sheng Ang noted how he had to research Malaysian and Indian kitchens, describing how he had to go beyond his comfort zone to appropriately illustrate his message of multiculturalism (fig 5).

Fig 5: Qing Sheng Ang (“Tangle Lah!”, 2022) speaking during the Q&A of Asia Road 3.

Fig 5: Qing Sheng Ang (“Tangle Lah!”, 2022) speaking during the Q&A of Asia Road 3.

In fact, some of the younger animators I met during the festival (over grilling pork belly, no less) made similar comments about transnational connections. Their interview ended up being a much more multicultural and multilingual conversation than I had initially expected. We had to finagle between English, Japanese, and Mandarin, switching between translation apps and the polyglots in the group. Moreover, three out of the four directors are currently based outside of Sinophone lands. Han Xiaoxuan (Don’t Forget to Take Your Medicines on Time, 2023) lives in Beijing; Shi Shengxue and Chen Lindong (Return, 2023) are currently studying in Tokyo; Singapore-born Clarisse Chua (Goose Quest, 2022) works at Skydance Animation in the Los Angeles (fig 6). All four of them, however, bristled at the idea that their animation is necessarily “Chinese” because they themselves are ethnically Chinese.

Fig 6: From left to right: Han Xiaoxuan, Chen Lindong, Shi Shengxue, and Clarisse Chua

Fig 6: From left to right: Han Xiaoxuan, Chen Lindong, Shi Shengxue, and Clarisse Chua

Han Xiaoxuan asserted, “Maybe it’s different for me because I don’t have any words in my film, but I don’t think ‘national frameworks’ matter so much to me. There’s not so much difference between us as individuals, whether we are Korean or Chinese.” After some brooding, Chen Lindong agreed, “Just because I am Chinese does not mean that all the animation I make is ‘Chinese animation;’ that is a more accurate descriptor of state-sponsored animation. My art has no national borders.” Shi Shengxue similarly sympathized, “Animation is the language I chose, not ‘Japanese’ or ‘Chinese’ animation in particular.”

Eschewing labels gets tricky in the US and on the international film circuit, however, as Clarisse Chua pointed out. In a landscape where identity labels hold weight and national affiliations coexist in festival programming, Chua recounted how she was surprised that she had the option to add both “USA” and “Singapore” to her competition entry. “Since I made Goose Quest (fig 7) in the US, I initially just checked off the “USA” box. I could have made this film anywhere,” she recalled, “But this festival contacted me first to make sure that I was from Singapore, so that the entry could be included in Asia Road.”

I asked her if she would categorize her film — a 4:3, 8-bit ode to a goose’s simple journey to turn back time — as American, Chinese, or Singaporean. She shook her head. Reflecting upon her childhood, Clarisse Chua noted, “Growing up in Singapore, all the media I consumed was from overseas, whether it’s Japanese anime or American movies or Chinese and Korean dramas,” she said, “I feel like animation is globalized.”

Fig 7: A still from Goose Quest (2022), by Clarisse Chua.

Fig 7: A still from Goose Quest (2022), by Clarisse Chua.

I admit, I walked away from these conversations a bit perplexed. I was assigned to write a report on Chinese animation, after all! At the same time, however, I was reminded of my own attraction to the field. For example, at an earlier edition of Indie-Anifest, in 2019, I realized that most attendees did not live just in Seoul. The Korean filmmakers I talked to then shared how they moved around, from places as close as the Seoul suburbs to as far as Japan, France, and the UK. The non-industry folks likewise recounted their trans-Pacific biographies, relating how they too had to juggle between North American and East Asian standards. Within this space of transnational folks in animation, I remember feeling for the first time, that I belonged somewhere. Here, at Indie-Anifest, identity felt plastic and mobile, much like an animated figure transforming, one frame at a time.

Still, to parse apart these ideas further, I approached Lee Kyung Hwa, the Head Programmer of Asia Road since its founding in 2016. We spoke on the last day, amid the liveliness of the CGV lobby, where audiences and animators alike lounged about waiting for the closing ceremony (fig 8). “Originally, when I thought about your interview inquiry, I thought about works from Taiwan, China, and Hong Kong,” she said. Further, she reflected, “But if we want to take it further, we could also include Singapore and Malaysia, not to mention the many [ethnically Chinese] students who are either born or studying abroad, like in Germany or Japan. It gets complicated. Where does ‘Chinese animation’ even start and end?”

I relayed my conversation with the animators to her. She responded, “Independent animators want to express themselves, not their citizenship. Besides, rather than differences between national cinemas, I think it’s more about a difference in schools. There’s a distinct stylistic difference between students who graduated from, say, the Communication University of China, or from GOBELINS Paris.”

“Of course, there are also differences in the stories that people can tell, too,” said Lee Kyung-hwa. To which she continued, “Someone who lived in Karachi will, for example, have a different relationship to the city than someone who is not, and thus make a totally different film. Otherwise, the differences are really based on where the animators, regardless of their origins, learn their craft.”

Fig 8: The author and Lee Kyung Hwa, on a polaroid distributed at the Indie-Anifest Flea Market in the CGV Lobby.

Fig 8: The author and Lee Kyung Hwa, on a polaroid distributed at the Indie-Anifest Flea Market in the CGV Lobby.

And, according to Lee Kyung Hwa, regardless of regional politics between Korea and the Sinophone world, Korean audiences — especially in independent animation — flock more towards good craftsmanship before considering home origin. As she said, “Even Disney and Pixar movies aren’t guaranteed to sell well here. It’s all about the quality of the work.”

Because I am currently based in Silicon Valley, where talk about AI is all the rage, I decided to finally ask Lee Kyung Hwa where she sees the future of animation going. “Last year, we started to receive more works animated with AI, especially from China,” she noted, and then continued “We’re also seeing a rise in media art – which becomes more of an existential question for a festival like ours, which celebrates independent animation. In the end, since our venues are usually in movie theaters, we try to select for films that would best suit a traditional cinema.”

This conversation reminded me of Shanghai-based artist Lu Yang’s The Great Adventure of Material World (2020), which I had seen just two weeks before at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. In this eight-episode series about a knight traversing through heaven, hell, and outer space, Great Adventure unapologetically introduces a worldly, Internet cosmopolitanism. National boundaries and everyday particularities matter little in Lu Yang’s CGI universe (fig 9). By mashing together references ranging from Sailor Moon-inspired uniforms to multi-armed, heavenly beings from Buddhist mythology, Lu Yang seemed to showcase the infinite possibility of “Chinese animation,” as echoed by the interviewees at Indie-Anifest.

Fig 9: A still from The Great Adventure of Material World (Lu Yang, 2020). Courtesy of luyang.asia.

Fig 9: A still from The Great Adventure of Material World (Lu Yang, 2020). Courtesy of luyang.asia.

At the closing ceremony, Indie-Anifest presented awards that moved towards more multicultural subjects. Perhaps part of this is due to the international nature of the judging team itself, which included US-based Emily Dean and Park Jeeyoon, and Oh Seoro, who used to live intermittently in Japan. The Grand Prize of Asia Road, “Light of Asia,” went to Wedding on the Execution Ground (Zilai Feng, 2023). Trained in Los Angeles and now a story artist at Pixar, Zilai Feng is also an example of Lee Kyung-hwa’s comment on international mobility. The story too was a heart-wrenching take on diasporic reunion. Here, a retired actress from a 1960s Chinese propaganda play, prepares herself to meet her first love, who had returned to their hometown 40 years after his move to Canada (fig 10).

Fig 10: A still from Wedding on the Execution Ground (Zilai Feng, 2023).

Fig 10: A still from Wedding on the Execution Ground (Zilai Feng, 2023).

Of the other three awards in Asia Road, two of them were given to filmmakers of Chinese descent. The Jury Special Prize went to Goose Quest (Clarisse Chua), and the Prize for Asia Road, CHACHA (Chenghua Yang and Shang Zhang). Iranian filmmaker Yagane Moghaddam took home the Audience Choice, “Star of Festival” for her textile-based memoir, Our Uniform (2023). And, in Mirinae Road, Indie-Anifest’s features competition, Lei Lei’s clay-and-cutout family history, Silver Bird and Rainbow Fish (2022) walked away with the Jury Special Prize (fig 11).

Fig 11: A still from Silver Bird and Rainbow Fish (Lei Lei, 2022).

Fig 11: A still from Silver Bird and Rainbow Fish (Lei Lei, 2022).

All in all, I think that — more than anything — this report has been a stark learning curve for me. I came into this project with an informal background in contemporary Chinese animation, familiar with the occasional Ne Zha remake or independent Taiwanese feature. Researching at Indie-Anifest had me thinking not about what Chinese animation was, as in the SICAF report, but rather about what Chinese animation could be.

In this vein, I find the questions of Han Ji-won’s short — ‘Where are we going? What will we become?” — all the more pressing. In a world where national borders get stricter day-by-day, I wonder if we can think about independent animation as a more porous, liberatory space of self-expression. Perhaps through animation, we can find a way to explore, rather than elide, personal and family histories. Perhaps, through animation, we can dream of radical futurities. And perhaps, through “Chinese animation,” we can think of this label as more expansive than exclusive — paving the path to a multitude of potentialities.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to extend my gratitude to Daisy Yan Du, Lee Kyung Hwa, Clarisse Chua, Shi Shengxue, Chen Lindong, Han Xiaoxuan, and all the Indie-Anifest staff for making this essay possible.

Bio:

Grace Han is a PhD candidate in Art History at Stanford University, where she thinks about animation aesthetics. Prior to coming to Stanford, she received the SAS Maureen Furniss Award for Best Student Paper on Animated Media (2019) for an essay on anime melodrama. Presently, she serves as the graduate representative for the SCMS Animated Media SIG and co-runs the Digital Aesthetics Workshop at the Stanford Humanities Center. She likes to read comics and garden (that is, touch grass) in her free time.